“The family unit is to be recognised as the fundamental basis of our society.”

Article 1 of the Goals and Directives of the PNG Constitution articulates the importance of the family to the development of the country. The right to have a family is further enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as Article 16 states, “The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.”

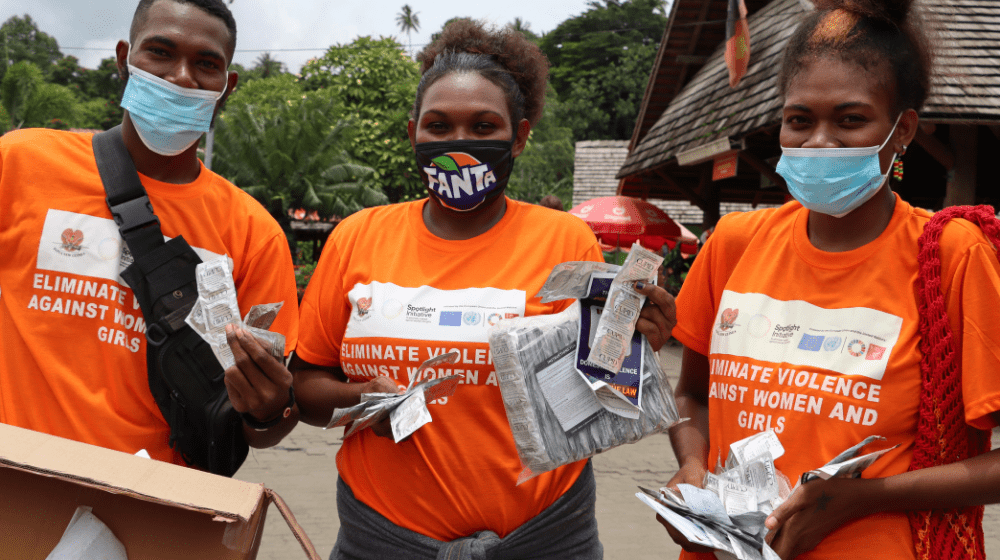

UNFPA, as the sexual and reproductive health agency of the United Nations, promotes access to family planning services and information for all men and women in Papua New Guinea.

It is often misunderstood, but family planning does not only mean planning not to have a family - though some people do make that choice. Family planning also means planning for a family in which every pregnancy is wanted, every childbirth is safe for mothers and babies, and every young person's potential is fulfilled.

Advocating for family planning means advocating for healthy families where mothers have reduced risk of preventable death during childbirth, where children can be cared for and nurtured - physically and emotionally - by parents who are present for them and can financially support children with their health and education.

It means advocating for a Papua New Guinea where women are not dying preventable deaths during childbirth.

Papua New Guinea has the highest maternal mortality rate in Melanesia. For every 100,000 births, 171mothers die.

In Solomon Islands that number is 104. In Vanuatu, it is 72. In Fiji, it is just 34.

In Fiji, 100% of births are attended by skilled health personnel. In Papua New Guinea, just 56% of births are attended by health personnel.

How can we accept that Papua New Guinean women and girls are dying in childbirth at higher rates than our Melanesian neighbours?

Of course, we shouldn’t.

UNFPA works with the National Department of Health and other partners to strengthen Papua New Guinea’s midwifery workforce with updated knowledge and skills on available equipment, medicines, and technologies to prevent maternal deaths. We work to get equipment and medicines to where they are needed, when they are needed. But the best equipped and most skilled healthcare workforce is only as successful as they are accessible.

We know that many remote communities lack access to healthcare and, while acknowledging the mountainous terrain and waterways of PNG make transport difficult, we can’t use the excuse of geography as a crutch for avoiding conversations about family planning and sexual and reproductive health.

The right to have a family doesn’t stop where the highway ends, and neither should access to sexual and reproductive health information and services, including family planning. Adequate access to family planning means the expertise and technology that is being built in PNG can be utilised to end maternal and newborn deaths.

And that access requires information. After all, how can we ask for something that we don’t know exists and how can we seek medical help when we don't know that something small may be a symptom of something bigger?

We can’t wait until a girl drops out of school because she is pregnant to tell our youth about contraception. We can’t wait until a woman is suffering from postpartum hemorrhage in a remote village to tell her that it is safest to wait two years between pregnancies. We can’t wait until a woman has experienced years of incontinence to explain obstetric fistula, how it can be prevented by having a skilled birth attendant and that there are simple surgeries to remedy it.

We can’t wait until a mother and baby both die in childbirth to tell the family that the blurred vision and headaches she spoke of were a sign of pre-eclampsia.

These simple pieces of information, building the nation’s health literacy, can save lives and make families stronger

Importantly, we need to be proactive in empowering women with the information that they need to make decisions about their own health and wellbeing and the health and wellbeing of their families. A woman is more than her uterus.

The 21st century has gifted us with access to information, but cursed us with incomplete knowledge and eroded trust in scientific facts. To protect our children we deny them knowledge that could prevent unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections and intimate partner violence. Our silence drives teenagers to seek answers online or among peers who are just as dangerously misinformed. The truth is that young lives are ruined because as parents, teachers, community leaders, we lack the courage to challenge a social norm that endangers our children.

We need to tell young people what contraceptives are available, how they work, and their benefits and side effects. We need to tell women and their partner that having a child within two years of a previous delivery risks low-birth weight, premature delivery, or hemorrhage. Men must be aware how to better support their partners, and that caring for them is a strength not a weakness. We need to tell women of early warning signs of common complications so that they can seek out care early and conditions can be managed. We need to ensure all families know that births should be attended by a skilled professional who can respond to complications.

We need to be sharing this information out in our communities, not in emergency rooms.

We need to talk about the numbers, because we shouldn’t accept them. We need to know this isn’t normal. Those who oppose family planning discussions and access to family services, who deny individuals and families their right to make decisions about their health and wellbeing, are not advocating for families, and they are not protecting our children. We need to advocate for better information on family planning for all who need it because that is how we protect families in PNG.